When the Docker Desktop application starts, it copies the /.docker/certs.d folder on your Mac to the /etc/docker/certs.d directory on Moby (the Docker Desktop xhyve virtual machine). You need to restart Docker Desktop after making any changes to the keychain or to the /.docker/certs.d directory in order for the changes to take effect.

- This is because Ext4 is a Linux file system and is not supported by the Windows operating system by default. Windows, on the other hand, uses the NTFS file system; thus, if your PC has important files that are saved on an Ext4 partition, you must mount the Ext4 partition to grant Windows access to read the files and allow you to modify them.

- I've found that creating a CoreOS VM under Parallels, then using the Docker that is inside CoreOS is far faster than Docker for Mac (currently running Version 17.12.0-ce-mac49 (21995)). I'm doing Linux code builds using CMAKE/Ninja/GCC and it's almost twice as fast as the exact same build from Docker for Mac.

Estimated reading time: 11 minutes

Btrfs is a next generation copy-on-write filesystem that supports many advancedstorage technologies that make it a good fit for Docker. Btrfs is included inthe mainline Linux kernel.

Docker’s btrfs storage driver leverages many Btrfs features for image andcontainer management. Among these features are block-level operations, thinprovisioning, copy-on-write snapshots, and ease of administration. You caneasily combine multiple physical block devices into a single Btrfs filesystem.

This article refers to Docker’s Btrfs storage driver as btrfs and the overallBtrfs Filesystem as Btrfs.

Note: The btrfs storage driver is only supported on Docker Engine - Community on Ubuntu or Debian.

Prerequisites

btrfs is supported if you meet the following prerequisites:

Docker Engine - Community: For Docker Engine - Community,

btrfsis only recommended on Ubuntu or Debian.Changing the storage driver makes any containers you have alreadycreated inaccessible on the local system. Use

docker saveto save containers,and push existing images to Docker Hub or a private repository, so that younot need to re-create them later.btrfsrequires a dedicated block storage device such as a physical disk. Thisblock device must be formatted for Btrfs and mounted into/var/lib/docker/.The configuration instructions below walk you through this procedure. Bydefault, the SLES/filesystem is formatted with BTRFS, so for SLES, you donot need to use a separate block device, but you can choose to do so forperformance reasons.btrfssupport must exist in your kernel. To check this, run the followingcommand:To manage BTRFS filesystems at the level of the operating system, you need the

btrfscommand. If you do not have this command, install thebtrfsprogspackage (SLES) orbtrfs-toolspackage (Ubuntu).

Configure Docker to use the btrfs storage driver

This procedure is essentially identical on SLES and Ubuntu.

Stop Docker.

Copy the contents of

/var/lib/docker/to a backup location, then emptythe contents of/var/lib/docker/:Format your dedicated block device or devices as a Btrfs filesystem. Thisexample assumes that you are using two block devices called

/dev/xvdfand/dev/xvdg. Double-check the block device names because this is adestructive operation.There are many more options for Btrfs, including striping and RAID. See theBtrfs documentation.

Mount the new Btrfs filesystem on the

/var/lib/docker/mount point. Youcan specify any of the block devices used to create the Btrfs filesystem.Don’t forget to make the change permanent across reboots by adding anentry to

/etc/fstab.Copy the contents of

/var/lib/docker.bkto/var/lib/docker/.Configure Docker to use the

btrfsstorage driver. This is required eventhough/var/lib/docker/is now using a Btrfs filesystem.Edit or create the file/etc/docker/daemon.json. If it is a new file, addthe following contents. If it is an existing file, add the key and valueonly, being careful to end the line with a comma if it is not the finalline before an ending curly bracket (}).See all storage options for each storage driver in thedaemon reference documentation

Start Docker. After it is running, verify that

btrfsis being used as thestorage driver.When you are ready, remove the

/var/lib/docker.bkdirectory.

Manage a Btrfs volume

One of the benefits of Btrfs is the ease of managing Btrfs filesystems withoutthe need to unmount the filesystem or restart Docker.

When space gets low, Btrfs automatically expands the volume in chunks ofroughly 1 GB.

To add a block device to a Btrfs volume, use the btrfs device add andbtrfs filesystem balance commands.

Note: While you can do these operations with Docker running, performancesuffers. It might be best to plan an outage window to balance the Btrfsfilesystem.

How the btrfs storage driver works

The btrfs storage driver works differently from devicemapper or otherstorage drivers in that your entire /var/lib/docker/ directory is stored on aBtrfs volume.

Image and container layers on-disk

Information about image layers and writable container layers is stored in/var/lib/docker/btrfs/subvolumes/. This subdirectory contains one directoryper image or container layer, with the unified filesystem built from a layerplus all its parent layers. Subvolumes are natively copy-on-write and have spaceallocated to them on-demand from an underlying storage pool. They can also benested and snapshotted. The diagram below shows 4 subvolumes. ‘Subvolume 2’ and‘Subvolume 3’ are nested, whereas ‘Subvolume 4’ shows its own internal directorytree.

Only the base layer of an image is stored as a true subvolume. All the otherlayers are stored as snapshots, which only contain the differences introducedin that layer. You can create snapshots of snapshots as shown in the diagrambelow.

On disk, snapshots look and feel just like subvolumes, but in reality they aremuch smaller and more space-efficient. Copy-on-write is used to maximize storageefficiency and minimize layer size, and writes in the container’s writable layerare managed at the block level. The following image shows a subvolume and itssnapshot sharing data.

For maximum efficiency, when a container needs more space, it is allocated inchunks of roughly 1 GB in size.

Docker’s btrfs storage driver stores every image layer and container in itsown Btrfs subvolume or snapshot. The base layer of an image is stored as asubvolume whereas child image layers and containers are stored as snapshots.This is shown in the diagram below.

The high level process for creating images and containers on Docker hostsrunning the btrfs driver is as follows:

The image’s base layer is stored in a Btrfs subvolume under

/var/lib/docker/btrfs/subvolumes.Subsequent image layers are stored as a Btrfs snapshot of the parentlayer’s subvolume or snapshot, but with the changes introduced by thislayer. These differences are stored at the block level.

The container’s writable layer is a Btrfs snapshot of the final image layer,with the differences introduced by the running container. These differencesare stored at the block level.

How container reads and writes work with btrfs

Linux Shrink Ext4 Partition

Reading files

A container is a space-efficient snapshot of an image. Metadata in the snapshotpoints to the actual data blocks in the storage pool. This is the same as witha subvolume. Therefore, reads performed against a snapshot are essentially thesame as reads performed against a subvolume.

Writing files

Writing new files: Writing a new file to a container invokes an allocate-on-demandoperation to allocate new data block to the container’s snapshot. The file isthen written to this new space. The allocate-on-demand operation is native toall writes with Btrfs and is the same as writing new data to a subvolume. As aresult, writing new files to a container’s snapshot operates at native Btrfsspeeds.

Modifying existing files: Updating an existing file in a container is a copy-on-writeoperation (redirect-on-write is the Btrfs terminology). The original data isread from the layer where the file currently exists, and only the modifiedblocks are written into the container’s writable layer. Next, the Btrfs driverupdates the filesystem metadata in the snapshot to point to this new data.This behavior incurs very little overhead.

Deleting files or directories: If a container deletes a file or directorythat exists in a lower layer, Btrfs masks the existence of the file ordirectory in the lower layer. If a container creates a file and then deletesit, this operation is performed in the Btrfs filesystem itself and the spaceis reclaimed.

With Btrfs, writing and updating lots of small files can result in slowperformance.

Btrfs and Docker performance

There are several factors that influence Docker’s performance under the btrfsstorage driver.

Note: Many of these factors are mitigated by using Docker volumes forwrite-heavy workloads, rather than relying on storing data in the container’swritable layer. However, in the case of Btrfs, Docker volumes still sufferfrom these draw-backs unless /var/lib/docker/volumes/ is not backed byBtrfs.

Page caching. Btrfs does not support page cache sharing. This means thateach process accessing the same file copies the file into the Docker hosts’smemory. As a result, the

btrfsdriver may not be the best choicehigh-density use cases such as PaaS.Small writes. Containers performing lots of small writes (this usagepattern matches what happens when you start and stop many containers in a shortperiod of time, as well) can lead to poor use of Btrfs chunks. This canprematurely fill the Btrfs filesystem and lead to out-of-space conditions onyour Docker host. Use

btrfs filesys showto closely monitor the amount offree space on your Btrfs device.Sequential writes. Btrfs uses a journaling technique when writing to disk.This can impact the performance of sequential writes, reducing performance byup to 50%.

Fragmentation. Fragmentation is a natural byproduct of copy-on-writefilesystems like Btrfs. Many small random writes can compound this issue.Fragmentation can manifest as CPU spikes when using SSDs or head thrashingwhen using spinning disks. Either of these issues can harm performance.

If your Linux kernel version is 3.9 or higher, you can enable the

autodefragfeature when mounting a Btrfs volume. Test this feature on your own workloadsbefore deploying it into production, as some tests have shown a negativeimpact on performance.SSD performance: Btrfs includes native optimizations for SSD media.To enable these features, mount the Btrfs filesystem with the

-o ssdmountoption. These optimizations include enhanced SSD write performance by avoidingoptimization such as seek optimizations which do not apply to solid-statemedia.Balance Btrfs filesystems often: Use operating system utilities such as a

cronjob to balance the Btrfs filesystem regularly, during non-peak hours.This reclaims unallocated blocks and helps to prevent the filesystem fromfilling up unnecessarily. You cannot rebalance a totally full Btrfsfilesystem unless you add additional physical block devices to the filesystem.See theBTRFS Wiki.Use fast storage: Solid-state drives (SSDs) provide faster reads andwrites than spinning disks.

Use volumes for write-heavy workloads: Volumes provide the best and mostpredictable performance for write-heavy workloads. This is because they bypassthe storage driver and do not incur any of the potential overheads introducedby thin provisioning and copy-on-write. Volumes have other benefits, such asallowing you to share data among containers and persisting even when norunning container is using them.

Related Information

container, storage, driver, BtrfsLately I’ve been using Warden to run some pretty large Magento sites not only with Docker Desktop for macOS but also on Docker running natively on Fedora 31 which I’ve got setup on a pretty sweet Dell T5820 I picked up recently. My local network is setup to resolve *.test domains to my Fedora setup when Docker Desktop is stopped allowing me to easily switch between the two, using VSCode Remote SSH + PHP Intelephense by Ben Mewburn as my editor and sometimes experimenting with PHP Storm over X11 in XQuartz. Perhaps I’ll blog about that as well some time, but for now, I’m going to move on to the primary topic of this post: MySQL write optimization on Linux as it pertains to I/O barriers.

The inspiration for this came to me while working on a Magento migration project for a relatively large site as I was testing a full database upgrade process. Now this database is not exactly what we would call “small” as it is 50 GB in size uncompressed. Even if you eliminate all the “extra” like reports, indexes, search tables, integration logs, etc it’s still 36 GB in size. Not super sized, but not too shabby either. For the purpose of the migration tests, I imported and ran with the 50 GB database dump, but for the A/B tests I ran to optimize MySQL on Fedora I was importing the smaller (yet still pretty sizable) 36 GB data set, which compresses down to just under 4.2 GiB in size.

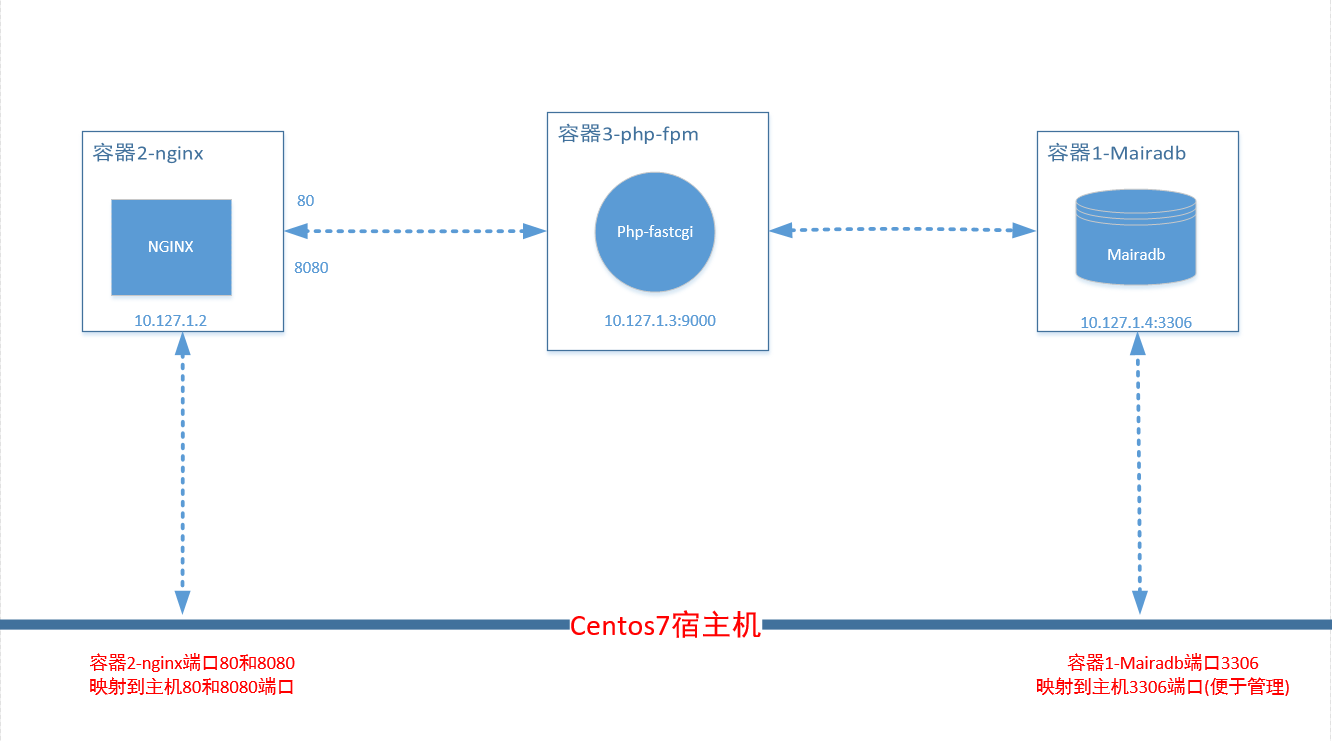

Importing this 4.2 GiB compressed SQL dump into the MariaDB 10.3 container on my Mac mini took only 2 hrs and 20 minutes, but importing into the same MariaDB 10.3 container running natively on Fedora 31 took a whopping 4.5 hrs. So immediately I asked myself, why would importing onto this Fedora machine (which has better specs than my Mac mini does) take so much longer? The Mac mini in question here has an onboard SSD, 32 GB of RAM and 3.2 Ghz clock-speed. Fedora 31 WS is running on a Dell T5820 with an i9-9920X CPU @ 3.50 GHz, 64 GB DDR4, 1 TB SDD M.2 NVMe (Samsung Evo Plus; LUKS + LVM). The biggest difference is on macOS the container is running within a VM and on Fedora the container is running natively and thus the docker volume is stored on the NVMe storage natively rather than in a virtualized storage format as it is on macOS. So why on earth was it slower when natively rather than virtualized? The answer lies in the understanding that a VM using virtualized storage results in a sort of disconnection between the virtualized kernel and the typical qcow2 or raw file the volume is written to on the host machine storage.

Disabling I/O Barriers for a 58% Reduced Import Time

The long in short of this is, I did two things to dramatically improve the time to import large database dumps (and better the I/O performance of MySQL across the board):

- Created an additional logical volume on my primary LUKS + LVM storage pool to provide more space than my boot partition has available to docker, but also so I could tune the mount separately.

- Formated the new volume as

ext4and mounted it at/var/lib/dockerwith thenoatimeandnobarriermount options.

The result of this was pulling the database import time down from a whopping 4.5 hrs to just 1 hr and 55 minutes. As you can see, write latency can really add up when doing sequential writes.

Note that the noatime option really doesn’t affect anything as far as write performance goes, because it essentially disables changing the atime of files on access improving read I/O performance (a micro-optimization by comparison), so I’m going to focus on the nobarrier option and what it does in the remainder of this post.

Before I dive into what nobarrier does and why it cuts database import time down so dramatically however, let’s see some numbers.

What My Partitioning Looks Like

The below is what my partitioning looks like. The SSD is encrypted with LUKS encryption, with LVM thin-provisioned partitions inside of the encrypted portion of the disk.

Importing with Default Mount Options

Importing with Custom Mount Options

The End Result

I realized a whopping 58% reduction in time spent importing this database dump due to setting nobarrier on the ext4 volume where MariaDB is storing it’s data on my Fedora development machine. This is incredible! If you’re using Linux for MySQL, whether natively or with containers, imagine the amount of time you could save as a developer by creating a separate volume to store that MySQL data with I/O barriers disabled. Remember, the performance benefit here isn’t just importing databases, it will improve the throughput on anything with lots of sequential writes due to the decreased latency during fsync operations.

Mac Slow Performance

And as always, an obligatory warning: Disabling barriers when disks cannot guarantee caches are properly written in case of power failure can lead to severe file system corruption and data loss. As I noted above, since I have a separate volume and a UPS (plus it’s a development machine) I don’t care too much about the risks here. It’s worth the tradeoffs for my use case. Don’t do this in production (unless you know with certainty that the write controllers in use will properly preserve data in the event of power loss)

Nitty Gritty Details About The nobarrier Option

So what is this nobarrier (or barrier=0) mount option? Here is what the man page has to say:

barrier=0 / barrier=1

This enables/disables barriers. barrier=0 disables it, barrier=1 enables it. Write barriers enforce proper on-disk ordering of journal commits, making volatile disk write caches safe to use, at some performance penalty. The ext3 filesystem enables write barriers by default. Be sure to enable barriers unless your disks are battery-backed one way or another. Otherwise you risk filesystem corruption in case of power failure (source)

In simple terms, a barrier is a check that occurs in the kernel and works together with journaled file systems to ensure data corruption will not result from sudden power loss. This I/O “barrier” (as will any single point through which data must flow) will bottleneck write I/O and slow it down. This same principle is part of why the NVMe protocol will perform WAY better than the older AHCI protocol: there are 64k command queues vs 1 command queue, and the media communicates directly with the CPUs rather than requiring the “middleman” communication with a SATA controller.

How much of a bottleneck I/O barriers will pose naturally will differ based on workload, storage medium, etc. Red Hat reports the performance impact of barriers as approximately 3% as of RHEL 6 and recommends not disabling them any more, but as we have seen this is not always the case. My guess (and it is a guess) is that this 3% mark RH mentions is more tied to benchmarks done with magnetic storage and more typical non-database write workloads (a web server for example is going to be impacted very little by this change since in most cases, it won’t be write heavy).

Further Reading Material

If you want to go deeper on the topic of I/O barriers and how they work, there is some good information available from Tejun Heo.

And lastly, there is a really good writeup on the PerconaDB site covering mount options like the above and more (such as queue scheduling; noop, deadline, cqp, etc) for tuning SQL performance across XFS, ext4 and ZFS. The post also touches on a few things around swappiness and NUMA interleaving. Good stuff.